Reconstruction of Ypres from 1919

Even before the Armistice on 11 November 1918 some of the local population were beginning to return to Ypres from their places of refuge in neighbouring parts of Flanders and France. Every building the locals had known was shattered and in ruins: houses, shops, municipal buildings, schools, the cathedral, churches, and the Lakenhalle (Cloth Hall) were gone. It was going to be a huge task to rebuild a whole town from its ancient roots.

With hundreds of men, women and children returning to Ypres there was a pressing need to accommodate them in new housing, to provide schools, medical facilities, shops, workplaces, the everyday facilities of a small town, and to rebuild the shattered infrastructure of drains, sewers and water systems.

Inhabitants Return

From July 1919 a subsidy was offered to those who wanted to return to Ypres and the surrounding ruined landscape of the Ypres Salient. The subsidy would help towards the costs of building basic accommodation to live in. Payment for war damages was also offered to help people make a new start building again on their old property.

Many people heading towards the destroyed city were seeking work as builders and construction workers. The better-off people tended to stay away from Ypres until much of the clearance work was done. Some wealthy land-owners sold their property, deciding not to be part of the reconstruction.

By 1920 the number of people living in Ypres was about 6,000. The population grew significantly during the 1920s and there were already about 15,000 people in the city by 1930. More than half of the 15,000 inhabitants were, however, people who had moved here after the war and had not been born and brought up in the city before 1914. Many of the families who had lived in and around Ypres for generations had decided not to come back.

King Albert Fund Housing

Already before the war was over the King Albert Fund had been set up in 1917 with the aim of planning ahead for the inhabitants who would one day hope to return to the devastated regions. It was intended that emergency, temporary housing accommodation could be made available in pre-fabricated sections which could be put up and dismantled easily.

The finances for these huts were provided from February 1919 by the Belgian Ministry of Internal Affairs (Ministerie van Binnenlandsche Zaken) and King Albert I, King of Belgium (1875-1934). The king had remained in Allied-held territory in Belgium throughout the war to lead the Belgian Army against the invasion by the Imperial German Army. He involved himself in the reconstruction of the areas which were devastated by the four year long war.

From the spring of 1919 lots of small prefabricated huts were put up to house the returning people of Ypres. The area of the Plaine d'Amour (Minneplein) in the north-west of the town was designated as a safe area for this temporary living accommodation.

The requirement by the returning inhabitants for these emergency huts far outweighed their availability in the early 1920s. Those who couldn't be given a hut were offered a subsidy with which to build their own basic house. The King Albert Fund was stopped in 1925. As a temporary housing measure it had been the government's intention to ask people to move out within a few years and the government would sell the huts. However, there were too many people still using them in the mid 1920s as their only accommodation so that idea was dropped. The local town authorities were encouraged to buy the huts off the government and some were lived in for many years.

One of the emergency huts still exists in Ypres and is lived in. It is located in a small street (with no name) between Schlachthuisstraat and Adjutant Masscheleinlaan in the north of the town.

Food & Provisions

Very little food could be produced in the area of Ypres in the early days after the war, and warehouses were opened during 1919 to store food and provisions to feed the returning local population.

Returning farmers began the enormous task of trying to salvage what they could of their farms, equipment and machinery. It would take some years to clear the land of abandoned military equipment, ammunition and bodies. Ploughing the ravaged fields could be extremely hazardous due to unexploded shells and collapsing underground tunnels. Also, a plague of mice ate through much of the crop growth in the fields in the 1920s.

Even in the 21st century dangerous ammunition is ploughed up by farmers or construction workers. The artillery shells, gas shells, grenades, bombs and bullets have become known as “The Iron Harvest”. Visitors to the battlefield areas are strongly advised never to touch anything like this that they may see or find - it may be unexploded ammunition.

Transport

The pavé (cobbled) roads had to be relaid and the dirt tracks and lanes rediscovered where they had been totally destroyed.

The railway lines were rebuilt and used to bring food and provisions into the area. It was also now possible to start to relax and for some people the pre-war popular day trips to the Belgian seaside could be enjoyed again.

The Ieper-Ijser (Ypres-Yser) canal was not reworked until the early 1930s. It was decided not to re-start the abandoned pre-war project to build the Ieper-Komen (Ypres-Comines) canal south of Ypres.

Public Administration

The local authority and the police were first based in huts on the Plaine d'Amour (Minneplein). After the Kasselrij building on the market place (Grote Markt) was reconstructed they moved in there.

Schools and the library also functioned from huts on the Minneplein for a few years until the rebuilt public buildings to house them were finished.

The town museum was re-housed from 1929 in the former Meat Hall near the western end of the Cloth Hall.

The post office building, one of the very few to survive complete destruction, was re-opened in 1923.

Public utility systems for gas, water and electricity were rebuilt.

Ypres as a Memorial

The idea of not reconstructing the city and leaving Ypres in ruins as a memorial had been suggested during the war. It was thought that a new city could be built nearby and not on the rubble of the destroyed city.

In July 1919 the British government succeeded in getting agreement from the Belgian government to create a “Zone of Silence” in the area of the destroyed Cloth Hall, belfry and St. Martin's cathedral. However, this was not willingly accepted by all of the local people in Ypres and after two years it was agreed that the British would be able to build a monument in Ypres instead. The location was agreed for the construction of a large memorial, the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing, to be built on the old eastern access route in and out of Ypres.

Reconstruction of Historic Ypres

|

The city architect, Jules Coomans, who had been overseeing the restoration of many of the historic buildings before the war, returned to Ypres from Boulogne-sur-Mer. He wanted to rebuild Ypres exactly in an image of what it had been before the destruction.

Although there were some who wanted to create a modern city with the clean lines of the architecture of the 1920s, those wanting to rebuild the old city in the Flemish medieval and renaissance styles won the discussion. King Albert was also one of the people promoting the reconstruction to be carried out as the original pre-war city had looked.

Once the agreement to rebuild the city as a replica of its ancient image was made in 1920, the work started on the public and private buildings in earnest. Lots of architects were invited to take part in the rebuilding, with Jules Coomans at their head. There were hundreds of builders and workmen employed in the reconstruction work, including many local returning inhabitants. Within five years much of the rebuilding work for private housing and most public buildings and utilities had been finished. Some public buildings were left to be completed in the 1930s. King Albert visited the city to see how the work was going.

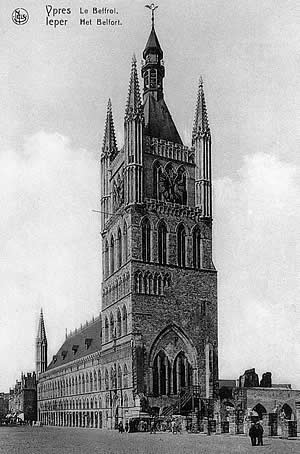

The Cloth Hall (Lakenhalle)

After great discussion it was decided to rebuild the Cloth Hall in the image of what it had looked like before its destruction. Architect Jules Coomans was in charge of the reconstruction. The work was started in 1928. In 1934 the western wing of the Cloth Hall and the belfry tower had been completed.

The eastern wing was not started at that time and only the pillars remained in their original location. Jules Coomans died in 1937 before the eastern wing could be started. An architect called P A Pawuwels took on the task of leading the rebuilding of the eastern wing and the Nieuwerk. The offices of the town administration moved into the eastern wing and Nieuwerk in 1967.

St. Martin's Cathedral

|

Interestingly, when St. Martin's Cathedral was rebuilt from its ruins under the leadership of Jules Coomans, the shape of the spire was changed. Pre-1914 the spire had been a square tower. During the period of restoration of Ypres' historic buildings leading up to 1914 Jules Coomans had had plans to change the cathedral spire to a pointed one. When the new “gothic” cathedral was finished in 1930 it had been rebuilt with a pointed spire.

The Lapidarium

The Lapidarium was the location of the St. Martin's monastery and cloister next to the cathedral. Jules Coomans's plans for the rebuilding of the cathedral did include the reconstruction of the monastery's cloisters. However, they were not rebuilt. The site of the monastery was one of the few places in Ypres which was kept as open ground as a memorial site and remnants of the cathedral and monastery were left there.

The Cloister Gate (Kloosterpoort)

|

The cloister or monastery gate of St. Martin's cathedral was one of the few structures which was not completely demolished by the end of the war. It was still standing while almost everything around it in the immediate vicinity was reduced to piles of rubble. It had stood since about 1780 and had withstood the terrible bombardments. It was restored in 1938.

Pilgrims and Tourists

|

From 1919 there was also an influx of visitors to Ypres. The city had become a focus for many people wanting to visit the Ypres Salient battlefields. These visitors were travelling to the battlefields of Flanders to visit the graves of their loved ones lost in the fighting. Some came privately, others travelled with organized tours. Some believed they might even find a relative or friend still alive who had been reported as “missing in action”. Ex-soldiers returned to the old Ypres Salient to see the ground they had fought over. There were formal and private ceremonies and anniversary commemorations along with the unveiling of numerous memorials across the Ypres Salient.

Some soldiers returned with items they had rescued from the ruins of the churches or cathedrals, such as remnants of stone statues and altarcloths. Such items had been taken back home after their time in Ypres. A piece of gold-embroidered stumpwork from St. Pieterskerk was found in the personal effects of an elderly WW1 Veteran and it had been his wish to return it to Ypres one day. His family returned it at a special ceremony and concert held on 11 November 1993 at St. Martin's cathedral to mark the 85th anniversary of 1918.

Hotels and Cafés

Hotels, restaurants and cafés were rebuilt or built in response to the need to offer accommodation and food for the many pilgrims and visitors who began to make journeys to Ypres.

Ieper (Ypres) Today

|

Visitors travelling to Ypres for the first time are astonished to think that the busy, vibrant town they see today, with its medieval and renaissance architecture was completely flattened and that virtually the whole of the town was reconstructed stone by stone, brick by brick during the 1920's and 1930's.

In the mid 1990s the town square was dug up again and relaid. A First World War machine gun was found buried beneath the cobblestones, which had been relaid during the reconstruction in the 1920s and 1930s.

Recent buildings constructed in the last few decades sit comfortably side by side with the medieval style buildings. Ypres is a busy place with all the facilities one would expect to find for business and pleasure in one of the leading visitor destinations in Flanders.

Related Topic

Sights to See in Ypres/Ieper

A listing of places to see and visit in the town which relate to the First World War and the reconstructed buildings of particular historical significance:

Acknowledgements

(1) Postcard of the Cloth Hall (Lakenhalle) from a set printed in 1930 by Ern. Thill, Bruxelles.

(2) Postcard of St. Martin's cathedral from a set printed in 1930 by Ern. Thill, Bruxelles.

The Reconstruction of Ieper: A Walk Through History, by Dominiek Dendooven and Jan Dewilde